Excerpt: Even the Women Must Fight - Memories of War from North Vietnam

“Every book tells stories,

some intended, some not.”

-Lila Abu-Lughod, Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories, 1993.

“A woman is like a drop of rain

which can fall into a palace

or muddy rice fields.”

-Vietnamese proverb.

How it all began:

As I reflect on the history of this book, I am struck by the irony that it all began with a kitchen talk in Hanoi in 1993. It took me three years, listening to women tell their war stories, reading Vietnamese diaries and poetry, and watching the films that represent a lifetime of experiences by a female director and veteran of two wars before I began to understand how the American War affected the Vietnamese women who lived through it. For me, safe in a nation untouched by the direct brutality of war, the decade between 1965 and 1975 brought new opportunities to free myself from domestic definitions of the ideal woman. For women in Vietnam, those years brought so much death and destruction that dreams of returning home to normal family life sustained them. What I have come to see as my lucky distance from war might well have blinded me to the meanings of war, family, and the good life for Vietnamese women. Until one night in May 1993, when two Vietnamese friends let down their guard to talk about what the war meant to them.

We sat in the kitchen not because a Vietnamese kitchen is a cozy spot designed for conversation, but because it was the only place with good light and chairs. My husband, Tom Gottschang, and his colleague Dan Westbrook, in Vietnam to teach economics at Hanoi’s National Economics University, had rented a house on a busy market street in the center of the city. I was there to begin a comparative project on the legal status of women in China and Vietnam.

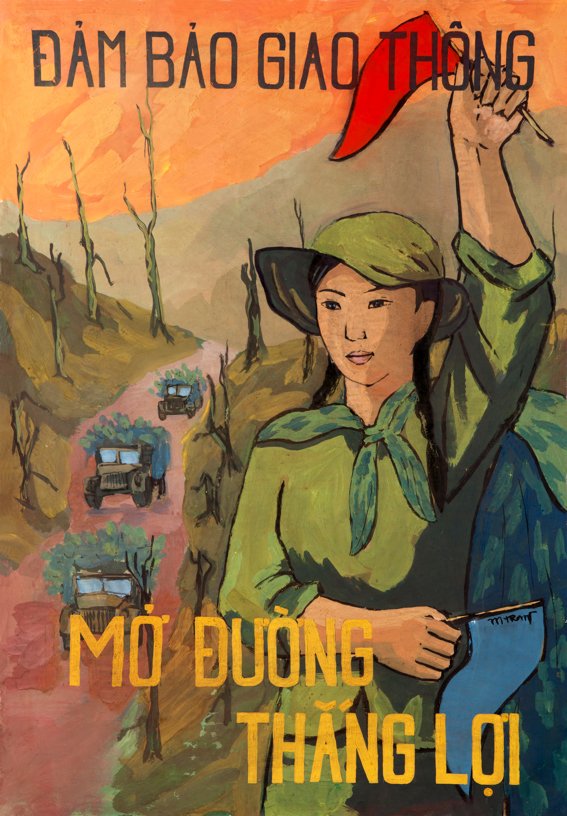

Our neighbor, Phan Thanh Hao, had brought us together to examine a series of paintings of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The artist, Nguyen Ngoc Tuan, a film studio set designer at the time, had carried his water colors as he walked down the Trail in 1974 to paint scenes for a film he wanted to produce. It was to be called “The Song of the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” to celebrate one of the most potent symbols of Vietnamese resistance to the United States. Funds for the film never materialized, and twenty years later his paintings had become important historical pieces, for they preserved the artist’s firsthand responses to wartime life. As we turned the paintings over one by one, to the clatter of tired ceiling fans and the hum of an ancient Russian refrigerator, we were surprised to find women in some of the pictures, engaged in the danger, the drudgery, and the camaraderie that make up any war. We asked whether the heavily burdened women crossing a mountain stream, the exhausted women shoveling gravel to fill a bomb crater, or the teenagers relaxing together in a secluded jungle station represented reality or the artist’s imagination.

Gender Dynamics

Tuan told us that these women were real indeed, that their presence on the Trail had moved him deeply. “They had a deep spirit, a love of life, even as they did the hardest work. And there were so many of them on the roads.” For him the Ho Chi Minh Trail was more than a maze of footpaths and roads, more than the main route for shipping supplies from the rear in the North to the regular army units and Viet Cong guerillas south of the seventeenth parallel. It was a potent symbol of Vietnamese patriotism and determination in the face of a technologically superior enemy. “The Trail,” he told us, “stays in my mind. It was the only road that would lead us to victory and everyone knew how hard it was to build it.” The women who used primitive tools to open and maintain the Trail represented for him the best traits of Vietnam itself: they were small but tough, ill-equipped but effective, romantic but realistic.

Women fording a stream on the Ho Chi Minh Trail,

painting by Nguyen Ngoc Tuan, 1974.

Crossing a rope bridge on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, painting by Nguyen Ngoc Tuan, 1974.

Hao was equally intrigued with the lore of the Ho Chi Minh Trail but more troubled about the consequences of Vietnam’s wars. A journalist in her mid-forties, a cosmopolitan person fluent in English and French, she was accustomed to dealing with foreigners who trekked to Hanoi in search of information and forgiveness. We didn’t know until that night that she had volunteered as a teenager to collect and bury the dead during the 1966 and 1967 bombings in the Hanoi area. This intimate contact with the carnage of war haunted her — especially the death of the young, who, as she put it, “had never known love, had never really lived.” For Hao, war meant nothing but suffering and sorrow.

How differently a woman and a man could interpret a common past, I thought at the time. As Tuan reminisced about the brave women who had inspired his paintings, Hao interrupted. Yes, she acknowledged, the women had been good soldiers. But they had paid dearly for their war service, in ways that men had not. With apologies to the men in the room for talking frankly, she explained that many women had lost their sexual health after years in the jungles, returning to their villages barren, unmarriageable, condemned to life on the margins in a society that values family above all else. Stress, backbreaking labor, malnutrition, contact with death and blood had eventually robbed these young girls of the very future they sought to defend when they left home in the first place.

Survivor’s Guilt

Most troubling to Hao was that the state had neither properly recognized the dead nor repaid the living. Plagued by what she often referred to as “survivor’s guilt,” she lamented as well that people like herself, with decent jobs and children, had no way to make it up to the veterans who had returned home wounded in body and spirit. In particular, she feared that women’s sacrifices might be overlooked, or their contributions trivialized, as Vietnam moves toward an open, market economy where youth and the competitive spirit will likely become more important than history, service, and community.

After that momentous talk, I began to comprehend how well Vietnam hides its war scars. Initially, I had been fooled — by Hanoi’s old buildings and markets, seemingly untouched by bombs, by the welcoming smiles of people ready to move to a pragmatic relationship with Americans — into thinking that the war was truly over, a distant memory. “Why do you want to talk about the war?” an interpreter in his thirties asked me. “We want to forget about it. It is only you Americans and the older people who think about it.” And an elderly veteran, now a high-ranking member of the Ministry of Defense, presented the official line to me during a luncheon meeting with his delegation at Harvard in 1996: “Women in the war? Yes, I remember how my mother supported me. It was our mothers who kept our spirits high, you know. But now Vietnam is ready to prosper and develop. We don’t want to dwell on the war.” I knew by then, however, that there was much more to the war story than mothers who stayed home while their sons did the fighting. And not all Vietnamese people were ready to welcome a new era without reflecting on the past.

Limited Perceptions

When I began to think about women, war, and Vietnam, I had to face up to my own ignorance of Vietnam’s postwar circumstances, to figure out why women warriors, so essential to Vietnam’s long history and so important in the most photographed war in history, have remained invisible to most Americans. To be sure, like many American women who came of age during the Vietnam War, I was fascinated and inspired by wartime media portraits of militiawomen and stories of martial heroines. In my own case, cautioned by my studies of Chines model women, who often represented the officials’ dream girls rather than real people, such superpatriots seemed to represent isolated cases or nationalistic propaganda. In the two images of women that did stick — Kim Phuc, the little girl running naked from a napalm attack, and a small militiawoman pointing a big gun at a downed American pilot — it was the link with our guilt and failures that left their mark. Women soldiers competently going about their business away from the American cameras never found a place in my memory.

Once the war was over and the embargo in place, like most Americans I lost touch with ongoing life in Vietnam. The image of the militiawomen faded away, as passive, inert female accessories to the American story — prostitutes, war brides, and displaced refugees — filtered through a media and literary world dominated by male veterans and filmmakers. This is not surprising, for “authentic” war stories are traditionally regarded as the exclusive domain of the men who experience combat firsthand. The women who supposedly linger on the sidelines, away from the real violence, stay in the shadows when the stories are retold. Anyone who reads the few accounts by American nurses who served in Vietnam feels their pain not only for the tragedies they witnessed but for their second-class status in the military and then the civilian worlds.

Vietnamese women too disappeared from their country’s record of struggle and victory, both in the United States and in Vietnam itself. Critic Kali Tal points out that Asian women have all too often been defined largely by their relationships with American men: “These fictional relationships with Asian women, whether mistresses or prostitutes, do not indicate any feeling on the part of either character or author that women are human beings deserving of respect.” She argues that the flat female characters in the Vietnam war stories produced in the United States reflect the reluctance of veteran male writers to come to terms with the dehumanizing effects of war. But I think that many of us accepted portraits of women as victims because they were less troubling than real life accounts of women’s all too human anger and daily struggles to survive. I sympathize with Susan Brownmiller, a television reporter during the war, as she recalls her reactions to the war era: “The truth was, I’d checked out of Vietnam emotionally a long time ago. I had ceased to follow its fortunes after the 1968 Tet Offensive, had renewed my interest during the 1973 Paris peace talks, then dropped it again until those awesome shots on TV of the last helicopters leaving Saigon. We need our defense mechanisms, and mine had been to disengage from the horror by skipping the news stories, by turning the page.”

Post-war Vietnam

In Vietnam, as hundreds of thousands of wounded men returned to their families and communities, as male veterans and reporters began to write about the war, public pity focused on the male veterans. Hao told me that “everyone felt sorry for the men. There were so many veterans and they had so clearly suffered so much. Everyone could see it. No one thought about the women then.” The few writings from Vietnam available in English portray the “people’s” war as one fought by men alone. Recently, the fiction of Vietnamese women veterans has started to appear in English. But most women veterans are not skilled with the pen, or have no access to the publications industry, and so ordinary women’s remembrances can be preserved only through oral histories.

Aware that much ink has been spilled over the limits and rewards of using oral histories, particularly when they involve a charged historical event, I knew that some veterans presented testimonials, which were directed at educating me and through me my American audience. These carefully crafted accounts often drew from a common reservoir of experience and myth. For example, several women recalled that they had pricked their fingers to draw blood to use as ink when they wrote letters to local authorities, begging them to overlook the fact that they were not yet old enough to serve in the youth corps. Most women did not wish to disengage their personal histories from the story of the national struggle, precisely because their individual lives took on meaning through their links with larger events.

It was from ongoing conversations, as women who became my friends retold their stories, filling in gaps as we came to know each other better, that details and differences in personal experiences emerged most clearly. These exchanges did not end when I left Vietnam. Not only with Hao, my coauthor, but with other women, e-mail and fax machines made possible a virtual dialogue, as I sent drafts to Vietnam to be read and critiqued. I was able to stay in touch with some of the veterans of a volunteer youth group, C814, through friends. In July 1997, Thu, one of the young women who had worked with me to interview the veterans of this troop, went to their annual reunion and read them passages from the sections of this book devoted to their memories. She wrote to tell me about it: “When I finished reading, you know, the troop leader shook my hand and said this was the first time he had listened to a real, moving story written by an American. I wish you had been there on that day.”

I wish I had been there too, to ask the questions I didn’t know enough to ask the first times we met, to hear for myself their responses, to observe firsthand their reactions to a foreign woman’s version of events that still trouble both sides.

Cooperation

In 1996, Hao and I began to work together, aided by English-speaking students from the University Job Placement and Consulting Program that she supervises. We were both cautious. I knew from nearly two decades of work in China that involving a colleague fro ma country suspicious of foreigners in even the most benign research project can be harmful to both parties. She had reason to be wary of outsiders whose proposals had at time spun off in directions she never anticipated. At the outset, we tried to be clear about how we would work together but maintain our separate voices. We decided that I would write the book and she would help me collect information and comment in writing on my presentations of interpretations and facts. This give and take was at times painful, and sometimes we could not honestly see eye-to-eye and simply agreed to disagree. As we discussed hard issues — what is true, whose stories carry more authentic information than others, what materials should be included, how the stories might be focused — we were learning more from each other than any book on discourse theory could offer. And I was hearing in the best way, through daily conversations, how nuanced one woman’s view of history and postwar culture could be.

The self-confident woman I first met in 1993, dressed in jeans and high heels, carried her hard past and present difficulties lightly, as did so many of the middle-aged women I met. One had to look carefully to discover their histories and troubles. Once I began to know Hao as a friend, I noticed things I had ignored before. In 1993, impressed by her modern house with its art-filled walls, our American household had fantasized that she was so powerful a force in the neighborhood that she had actually halted the early morning slaughter of pigs outside our bedroom window after I confessed that I plugged my ears against the inevitable morning screams. Later I discovered that it wasn’t Hao who chased the butchers away. She too felt vulnerable in the neighborhood as she negotiated constantly with the street vendors, who blocked her front door and then used her house as a hiding place when the police came around to check their licenses.

I learned, too, how Hao herself viewed us, the foreigners, when we first moved into the neighborhood. She told me that she had not known when we looked at the paintings of the Ho Chi Minh Trail together in 1993 that Tom had served in the U.S. army during the war: “So that night when we talked about the paintings in your house, I just thought that Tom’s sympathy was for the plight of the painter. Only later, when I knew Karen better, did I discover why Tom had been so somber when we looked at the paintings of the Trail — because they brought up his bad feelings about the past.”

We, the guilty Americans, were not the center of our Vietnamese friends’ universe. They had other matters on their minds: family dramas, friends who needed money, sick children, and jobs.

I found out over time that Hao’s life history was similar to mine only in that we had both married and become mothers at a very young age and had fought hard to gain an education. Socialist political campaigns had disrupted her childhood almost as much as war. She was the daughter of a famous poet and activist during the anti-French resistance and a woman from one of the old Hue mandarin families, and her family paid for its bourgeois background most dearly in 1954, when her paternal grandparents were killed in the radical land reforms. In 1965, as North Vietnam’s leaders geared up for an all-out war against the North, her father was arrested on vague charges that he had too many foreign ideas and possible counterrevolutionary sympathies. Her mother and siblings were treated at once as social and political outcasts, denied access to education, decent jobs, adequate food, and housing. But by the war’s end, by dint of hard work and a talent for languages, Hao had earned a place as a journalist and an interpreter.

I saw her as a prime exemplar of a woman who had made the best of her life through diligence and careful decisions. She felt that pure luck lurked behind any woman’s success, and that good fortune could all disappear in a flash, just as homes and people had disintegrated even before the noise of the B-52s could be heard over the skies of Hanoi during the war. As she and I talked about a title for this book, our differences came to the fore. I wanted a title that bespoke heroism, courage. She argued for something that pointed to victims, sorrow. I believed that Vietnamese women had for too long been dismissed in the United States precisely because we never saw their anger and their survival strategies.

As Hao and I talked over these thorny issues, the caution of a Vietnamese scholar now in the U.S. came back to me: “If the Vietnamese people are treated only as a bunch of overgrown children, Vietnamese women are often described as perfect models of femininity — submissive to the authority of their fathers and husbands, passive, dependent, and domesticated.” Professor Long goes on to argue that when the Vietnamese people are regarded as passive puppets, then it follows that they cannot act as the agents of their fates and have no business governing themselves. “The Vietnamese revolution, therefore, is a search for a new authoritarian master and a new security. This explanation not only denies the Vietnamese any real and rational grounds for having a revolution, but justifies the American intervention and its failure to install democracy in Vietnam.”